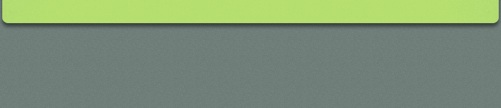

The Deutsch House at Gibb’s Farm

It all started when I was eight years old. I listened to the stories of neighbors who had returned from Africa. from then on I read all the available books about Africa, until I was allowed to be a soldier at age 16 1/2 in 1916.

Later I was a bank official in Argentina, traveled through Brazil as a business man, back in Germany I studied forestry, marked for the SA, and traveled through French North Africa as a newspaper journalist and came closer to my dream, when I met my wife, who also had a passion for Africa with her brother already settled as colonialist in East Africa. We used our savings and bought a piece of land in German East Africa that my brother-in-law recommenced to us.

In 1934 we made trip to Africa. Our land was on top of Oldeani Crater surrounded by beautiful landscape. On our way there, it was our honeymoon trip, we saw for the first time Mt Meru with the blue-green band of forest and soon thereafter we discovered through the clouds the snow cap of Kilimanjaro, which seemed like a picture from a strange world. Late afternoon we arrived in Arusha. We loved this little town right away, and still do. We went to the market place, looked at Massai women who wore heavy steel rings around their necks, arms and feet. We walked through the Indian quarters, underneath old cypress and eucalyptus trees and visited the Boma, a fort left from German times.

Today, it holds the town hall, police station, the court and more. We enjoyed the late afternoons, drinking coffee in the Barasa, watching half naked Massai with spears leading their herds through the streets.

We hired an Indian driver with an old truck and left with crates, suitcases, bales, lounge chairs, rabbits, corrugated sheet iron, hens wire fences an banana plants.

At our destination, my brother-in-law awaited us anxiously. He was very helpful showing and explaining to us all the things we hadn’t experienced or ever seen before. Our house was a small mud cottage with a cone shaped grass roof. Our land, the bigger part of it, consisted of a smaller, easterly slope on the west of a river. The house was built oat the highest spot of the ridge where the forest and brush land meet, overlooking all of the land.

We build our house

When we started to build in 1935, we didn’t know if we could. It was more out of necessity. Our lovely old round hut, made of loam and a straw roof sill exists today. For our guests it is a romantic place, but for use as a house it was more problematic. The only 35 square meters were divided into bedroom, dining room, studio and pantry. Packed in were tables, chairs, beds, suitcases, crates, pots, food, weapons, and books.

After pondering all possibilities we decided the cheapest and best way to proceed seems to use rocks and cement after we found a huge stone ledge near the building site. I would like to know whether an Architect at home knows in advance how much building material is needed.

We sure didn’t know, and everything we carry, pull and pile up, is never enough. Part of the answer is clear: because the dear native - as soon as you turn your back - waste the cement in big quantities so they can use the empty barrel to brew beer in.

We use powder and fuse to blast a big rock formation and for weeks the laborers carried enough rocks to to the house site. Tope, a reddish wet mud proved to be a very good building material. It ‘gives’ after it hardens and is often used in earthquake prone areas. We worked the tope throughout, except for the ground floor and attic were we put in a layer of cement, because of the termites, which could eat not only our garments, books, furniture, but also turn tour roof truss into wood powers. Slowly a kitchen, residential dwelling and smoke house appeared.

To get the three patio columns plumb proved challenging. All the blanks for the roof construction and ceiling were sawed in the woods, with the big two-handed saw. From morning to night, while also doing the plantation work for months we hammered and did masonry. The ceiling beams were tarred, the boards prepared with linseed oil. Windows and doors were delivered by the joiner from his workshop in Arusha. To lay the corrugated tin sheets accurately on the roof went easier than expected and so was putting gin the cement floor, which to this day is still without cracks.

We made built-in closets from gas crates and after scratching off the hard ‘tope’ on the walls, we filled the ridges between the stones with cement. How long it will last we don’t know. I guess it depends when the next earthquake will happen. The last thing to add was a fire place in the living room. I built it myself with my own hands, using ‘tope’ bricks. On the mantel i cemented in a small stone from castle Niederpeollnitz, Thueringen, where my family originated from in the 12h century. Underneath, I chiseled in my family’s coat of arms.

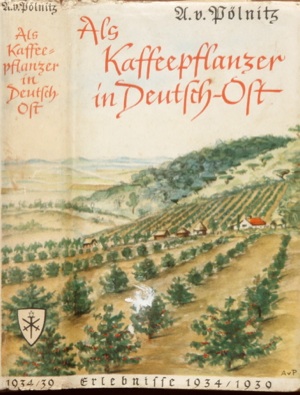

To describe the house, it was a big patio with columns and wicker furniture, next door is my studio. I can oversee from my window the courtyard and part of the plantation and a small part o the far away East African escarpment. In the higher built connector to the house was my wife’s room and the living room. Crate furniture and arm chairs covered with hides, spread on the floor were mats and small indian rugs. The walls are decorated with antelope antlers and engravings of hunting motifs by Ridinger. Bavarian, colorful curtains keep the midday sun out. Over the years the living room slowly became a magnificent room. On the longest wall above my self-built book shelves hangs the most gorgeous buffalo skull. On the wall across a European fourteen-ender deer from our home land. From the walls, our ancestors look at us in miniature, paper curtains and oil painting.

The building was successful, it is cool, rain proof and friendly. Bats, butterflies, bees and lizards share the house with use because we recklessly sleep with the doors and windows wide open. In front of the house a patio swings out in a half round an din front of it lies a flower garden. Throughout the year we have violets, carnations, oleander, lilies, cannas, snap dragons, chrysanthemums, eucalyptus, cedars and lilac. Near the house we don’t plant flowers because of the snakes, only the climbing rose bush grows on one corner, to hide he not so straight wall!

A German Colony

What was true for German Oldeani area was, that life was very hard, but no one cheated or lied to the other colonists, they all helped each other and not one of them lost their money.

Over sixty plantains lie between the Ngorongoro and the Oldeani ones. In between them are many helpful installations: school, hospital, a German store, post office, and a Indian store. It was affordable land, not unlike already cultivated properties. When ten years ago the first settles arrived, there was no local population nor water found here. The Wambulu, whose land it was, were afraid to enter it because of the plundering Massai. But now they come closer. On m border there was on e family found in 1933, n and now there are about fifty. The newcomers expect use of our water digs, and the stae officials pathetical flights for their rights.

The names of the different plantations tell stories too. ‘Camp yo Nyoka’ has many snakes; ‘Tembo deals with vistiros from elephants; ‘Kurpfalz, ‘Hannovera’, ‘Anhault’, and mine ‘Nova Franconia’ show there are many Germans for all over Germany. This helped form a tight community with the result that a former school hut is now a solidly build stone house. The old nurse station from 1933, a mud hut with grass roof, is now a sparkling clean hospital. Within ten years two and a half million coffee trees were planted and in 1938 four hundred tons of the finest coffee was harvested.

Planting Coffee and other Farm Work

In the beginning, everything seems easy and you believe 100% in your German European energy. Soon, you realize how much you don’t know, how little help your commons sense and your race’s physical strength are when you deal with nature in the tropics; how simple, like a child’s play it is to plant the coffee tree, but how difficult it is to tend it from the growing to the drying. Clearing grassland is least expensive, brush land takes effort and woodland is the most expensive and involved to cultivate.

To raise livestock is easier than in Europe because the herds are on the pasture throughout the year, and also because some of the natives are very good in dealing with animals. Treating the many diseases of the animals is an additional problem. And don’t forget all the work that needs to be done daily i the house, sheds and garden. Windows to be oiled, artichokes picked, mole traps restrung, wood piled. The fresh hide of a bush buck- the natives again put in the sun - can only be dried in the shade. The Japanese plums need to be covered so the birds will leave us at least half the harvest. My Laderhosen I mend myself, buy my wife does all the other sewing necessary. The worst of our tasks is the slaughtering. W hat do you do it the pig is still alive after a hit on his head, a shot behind the ear and a knife stabbed into the heart area? The life here is no pure fun nor enjoyment.

German East Africa

The first agent of German imperialism was Carl Peters, who, with Joachim, Count Pfeil and Karl Juhlke, evaded the sultan of Zanzibar late in 1884 to land on the mainland. He made a number of "contracts" in the Usambara area by which several chiefs were said to have surrendered their territory to him. Peters' activities were confirmed by Bismarck. By the Anglo-German Agreement of 1886 the sultan of Zanzibar's vaguely substantiated claims to dominion on the mainland were limited to a 10-mile-wide coastal strip, and Britain and Germany divided the hinterland between them as spheres of influence, the region to the south becoming known as German East Africa. Following the example of the British to the north, the Germans obtained a lease of the coastal strip from the sultan in 1888, but their tactlessness and fear of commercial competition led to a Muslim rising in August 1888. The rebellion was put down only after the intervention of the imperial German government and with the assistance of the British navy.

The enforcement of German overlordship was strongly resisted, but control was established by the beginning of the 20th century. Almost at once came a reaction to German methods of administration, the outbreak of the Maji Maji rising in 1905. Although there was little organization behind it, the rising spread over a considerable portion of southeastern Tanganyika and was not finally suppressed until 1907. It led to a reappraisal of German policy in East Africa. The imperial government had attempted to protect African land rights in 1895 but had failed in its objective in the Kilimanjaro area. Similarly, liberal labour legislation had not been properly implemented. The German government set up a separate Colonial Department in 1907, and more money was invested in East Africa. A more liberal form of administration rapidly replaced the previous semimilitary system.

World War I put an end to all German experiments. Blockaded by the British navy, the country could neither export produce nor get help from Germany. The British advance into German territory continued steadily from 1916 until the whole country was eventually occupied. The effects of the war upon Germany's achievements in East Africa were disastrous; the administration and economy were completely disrupted. In these circumstances the Africans reverted to their old social systems and their old form of subsistence farming. Under the Treaty of Versailles (1919), Britain received a League of Nations mandate to administer the territory except for Ruanda-Urundi, which came under Belgian administration, and the Kionga triangle, which went to Portugal.

Tanganyika Territory

Sir Horace Byatt, administrator of the captured territory and, from 1920 to 1924, first British governor and commander in chief of Tanganyika Territory (as it was then renamed, with the flag represented on the left up until 1963 independence ), enforced a period of recuperation before new development plans were set on foot. Between 1919 and 1961 the flag above represented the territory. A Land Ordinance (1923) ensured that African land rights were secure. Sir Donald Cameron, governor from 1925 to 1931, infused a new vigour into the country. He reorganized the system of native administration by the Native Authority Ordinance (1926) and the Native Courts Ordinance (1929). His object was to build up local government on the basis of traditional authorities, an aim that he pursued with doctrinaire enthusiasm and success. He attempted to silence the criticisms by Europeans that had been leveled against his predecessor by urging the creation of a Legislative Council in 1926 with a reasonable number of nonofficial members, both European and Asian. In his campaign to develop the country's economy, Cameron won a victory over opposition from Kenya by gaining the British government's approval for an extension of the Central Railway Line from Tabora to Mwanza (1928). His attitude toward European settlers was determined by their potential contribution to the country's economy. He was, therefore, surprised by the British government's reluctance to permit settlement in Tanganyika. The economic depression after 1929 resulted in the curtailment of many of Cameron's development proposals. In the 1930s, too, Tanganyika was hampered by fears that it might he handed back to Germany in response to Hitler's demands for overseas possessions.

At the outbreak of World War II Tanganyika's main task was to make itself as independent as possible of imported goods. Inevitably the retrenchment evident in the 1930s became still more severe, and, while prices for primary products soared, the value of money depreciated proportionately. Tanganyika's main objective after the war was to ensure that its program for economic recovery and development should go ahead. Constitutionally, the most important immediate postwar development was the British government's decision to place Tanganyika under UN trusteeship (1947). Under the terms of the trusteeship agreement, Britain was called upon to develop the political life of the territory, which, however, only gradually began to take shape in the 1950s with the growth of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU). The first two African members had been nominated to the Legislative Council in December 1945. This number was subsequently increased to four, with three Asian nonofficial members and four Europeans. An official majority was retained. In an important advance in 1955, the three races were given parity of representation on the unofficial side of the council with 10 nominated members each, and for a time it seemed as if this basis would persist. The first elections to the unofficial side of the council, however, enabled TANU to show its strength, for even among the European and Asian candidates only those supported by TANU were elected.

The sculpture on the mantle piece is by Charles Bies, a SANAA artist-in-residence. This is in the Shitani style (2). He thought it appropriate this house speak to the spirits, as is the purpose of this type of Makonde carving genre.

An old Makonde (1) from the original collection depicts a traveller carrying food, a gourd on his head and one near his feet. Its likely the gourd calabash at his feet is for carrying water or a beverage.

Dr. Albert Freiherr von Poelnitz account of the Gibb’s Farm community in the late 1930’s

Gibb’s Farmhouse as built by Dr. Albert Freiherr von Poelnitz

The Freiherr von Poelnitz family crest installed above the Deautch House mantel peice.

(1) Unkown artist Mpingo wood carving. Original Farm Collection.

(2) Charles Bies, Shitani, Mpingo wood carving.

Sanaa Art Gallery Collection installed in each cottage. Select works have been commissioned to carry the theme and lesson of the house.

Suite Fact Sheet Download (click left)

Click on photo slide show below

-

Other Gibb’s Farm web-links:

New Tourism & the Harmony Project, All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2004 - 2012

African Living Spa, and Living Spa ® are registered/trademarked.